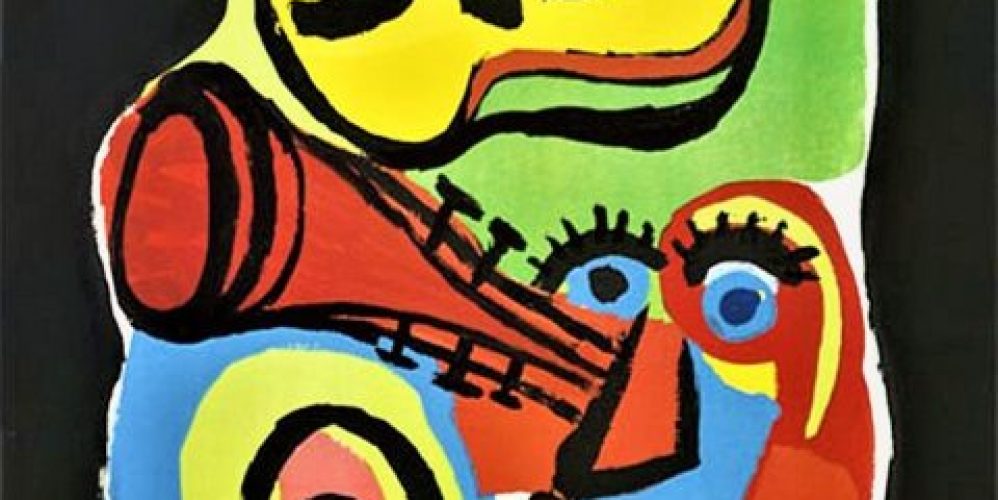

Wherever in the world you walk into a modern art museum, standing face-to-face with a work by Karel Appel (1921- 2006) is always a moment of joy. The paintings and sculptures of the Dutch artist, born in the Amsterdam Dapperstraat one hundred years ago, are vital, explosive, colourful and they are sparkling with life. His work may have become more abstract over the years, Appel distinguished himself from many of his contemporaries by not sinking into hopeless pessimism or haughty cynicism. Thanks to the childlike character of his work, it has always something hopeful about it. Appel retained his open-minded view of the world until his old age.

His way of working, driven by primitive instincts, often led to the misconception that Appel’s art could have been made by children. “My little sister can do that too,” Dutch museum visitors would scorn when they saw his work. The Netherlands is the only country that has never taken Appel entirely seriously. Appel made statements that, with hindsight, may not have been very wise. Self-mockery is seldom understood and often even used against you. Appel’s exclamation, “I paint, I mess about a bit,” intended to avoid elevating himself above the common people as an artist, came back to him like a boomerang and tarnished his own reputation. The film Jan Vrijman made about the artist in 1961 worked like oil on the fire: “I lay it on thickly now, I hit the paint on with brushes and palette-knives and my bare hands,” Appel said, before he suited the action to the word and gave the camera lens, hidden in the canvas, a terrific broadside.

In the same documentary, Karel Appel uttered the sentence that lies at the heart of his oeuvre: “I start from the matter”. For Appel an image was always more important than its meaning. He preferred to compose his sculptures from found objects, which he selected for their colour, texture or shape. It is significant that Appel drew inspiration from jazz music. Jazz musicians flourish when they can leave the lyrics of a song behind them to improvise freely. They start from a theme and create a new work of art on the spot. The original idea is only recognisable in its basis and musicians love to colour outside the lines. In the same way, Appel devised basic forms for his works in advance. He carefully mixed his paint until he achieved the hue and intensity he needed. Karel Appel mastered the technique like no other and knew exactly what he was doing.

Appel attended the Rijksacademie in Amsterdam in a period that was not art-friendly, to put it mildly. His later work would certainly have been labelled Entartete Kunst during the war. The fact that Appel did not distance himself more openly from the German occupier probably says more about his political naivety than about his possible Nazi sympathies. Appel was merely interested in art. He eagerly imbibed the art history lessons, about which he had received little at home (his father was a hairdresser). Karel Appel was inspired by predecessors such as Rembrandt and Van Gogh, both of whom were innovative and directional in their own time.

After the Second World War, Appel strongly resisted the suffocating narrow mindedness that once again got the Netherlands in its grip. He didn’t fight with words but with colours and shapes, with which he could express his rebellious feelings much better. Although Appel initially collaborated with kindred Europeans under the name CoBrA, he was pre-eminently a soloist. The primal impulses that originated from his soul found an outlet in his generously painted canvases and explosive sculptures. His boundless creative drive led to ever-expanding works of art, such as the 80-metre-long ‘Wall of energy’ that he painted for the National Energy Manifestation in Rotterdam in 1955.

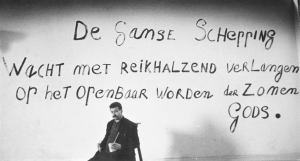

In 1957, Karel Appel designed six glass appliqué windows for the Paaskerk in Zaandam. Each window depicted a day of creation; the seventh day, the day of rest, was missing. The church council was less happy with the mural Appel painted. The words: “All of creation waits for God to reveal his children.” (Romans 8:19) disappeared under a new layer of paint.

Holland had become too small and too narrow minded for Appel, who was received enthusiastically in the United States. In New York, he became friends with his Rotterdam art brother Willem de Kooning, who had spread his wings for the same reason.

Appel was a productive artist who left an impressive oeuvre. In his later work, in which the Tuscan landscape plays a central role, the artist still created a wonderful balance between culture and nature, abstraction and reality. Karel Appel’s superior mastery of forms and colours left an indelible mark on the history of modern art.